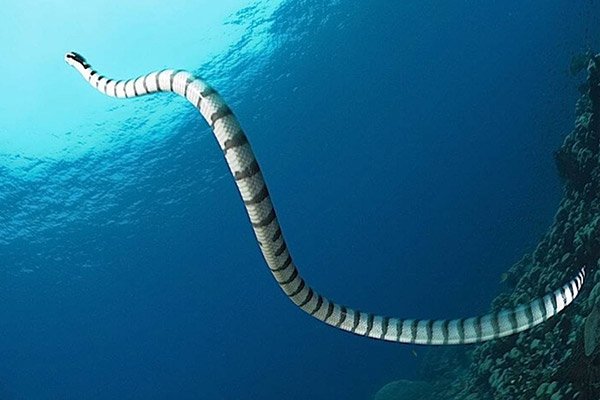

A common sight on the coral reefs of Southeast Asia, the banded sea kraits trigger excitement in some divers and fear in others. It’s a venomous snake! With its bold black and white bands, it’s easy to spot. It may seem threatening, but most likely, it’s completely uninterested in your existence.

What Divers Think and Fear

Yes, banded sea kraits are highly venomous. Their venom is about ten times more potent than that of a cobra, and a single adult has enough venom to kill ten humans. That’s the bad news.

The good news? They’re basically the ocean’s friendliest serial killers. These snakes are so docile and chill that they make Golden Retrievers look aggressive. They have enough chemical weaponry to take down a small army, but they’d rather just mind their own business.

Respect them, and admire them from a reasonable distance, and you’ll be fine. Try to catch them (especially on land), and you might win a very stupid prize.

The Science

Banded sea kraits, scientifically known as Laticauda colubrina are not actually “true” sea snakes. They’re sea kraits, which is different in some very cool ways.

True sea snakes give birth to live young in the water and rarely come ashore. Sea kraits are semi-aquatic, meaning they need both ocean and land to complete their life cycle. They hunt underwater, but they need to come back to land to digest their meals, rest, reproduce, drink fresh water, and shed their skin.

Banded sea kraits are commonly spotted at dive sites in Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and pretty much anywhere there’s warm water and coral reefs.

Beware Cheap Imitations

To make it extra confusing, there are also snake eels. These impostors have the same black and white banded patterns as Sea kraits. They boldly roam the sand and rubble during the day, pretending to be venomous and trying to impress potential predators (and divers, I guess).

However, these cheap imitations can easily be identified by looking at the shape of their head and the absence of scales. Unlike sea kraits, they often hide completely in the sand, and you’ll most likely see them with only their head poking out of the sand.

Snake Eel

Anatomy

Real Sea Kraits typically grow to about 80 cm to a meter in length. Their bodies are cylindrical and covered in scales, with distinctive black bands running from their neck to the tip of their tail. The tail is flattened like a paddle, which makes them excellent swimmers.

Their heads are small and slightly flattened. Perfect for probing into tight crevices where prey like to hide. And here’s a fun fact: their tails look remarkably similar to their heads. This is a clever defense mechanism. When they’re hunting with their heads stuck in a crack, their tail wiggles around and looks like a head, tricking predators into thinking they have two dangerous, venomous ends.

Deadly Bite

Let’s talk about that venom. Banded sea krait venom contains powerful neurotoxins that affect the muscles of the victim. When they bite their prey (eels, mostly), the toxin rapidly impairs swimming and breathing, basically turning a healthy eel into an easy-to-swallow meal within minutes.

The venom would cause similar effects in humans, but thankfully, that happens very rarely. Bites are most frequently sustained by fishermen who accidentally catch them in nets. For divers, the risk is close to none. Banded sea kraits are generally not aggressive and only bite in self-defense when accidentally provoked. Even if they bite, their fangs are relatively short, making envenomation difficult. A frightened snake may deliver a “dry bite” without injecting venom, as a defensive measure.

Here’s a fascinating fact: some moray eels have actually evolved resistance to sea krait venom. Moray eels from the Caribbean (where sea kraits don’t live) die from tiny doses, while morays from areas where sea kraits are common can tolerate up to 75 mg/kg without serious injury. It’s an evolutionary arms race, and the eels are fighting back.

They kill politely

Banded sea kraits feed almost exclusively on small Conger eels and Moray eels.

When they find an eel, they deliver a quick, venomous bite and then back off. Unlike many venomous snakes that hold onto their prey, sea kraits politely wait for the venom to take effect, then return to swallow their meal whole. After dinner, it’s difficult for them to swim, so straight after a meal, they head to land to digest their food in safety.

One of the coolest behaviors is their cooperative hunting strategy. Banded sea kraits have been observed hunting in packs with other kraits, and sometimes even teaming up with fish. The Krait will flush prey out of crevices while the fish is waiting on the other side.

Amphibious Lifestyle

Unlike snake eels, banded sea kraits are reptiles. They need to breathe air, so they need to surface regularly. Although they could stay underwater for six hours, they typically surface more often.

They also come ashore to digest their meals, to reproduce (laying about 10 eggs in rocky crevices), to shed their skin, to rest, and to drink fresh water.

Human Encounters

In some parts of their range, particularly in Okinawa and the Philippines, sea kraits are caught for their meat and skin. The meat is smoked and exported to Japan, where it’s used in traditional dishes like irabu soup (said to taste like miso and tuna).

Banded sea kraits are currently listed as “Least Concern” globally, which sounds great until you realize their habitat is declining fast. Coastal development, tourism, and climate change are threatening to destroy healthy coral reefs that sea kraits need for hunting and for reproduction.

Plastic waste is also a serious threat. Sea kraits can become entangled in debris or discarded fishing nets. If trapped underwater for too long, they drown (since they need to surface to breathe).

The good news is that sea kraits are highly adaptable. They can adapt to changing environments better than many species. But adaptability has its limits, and we shouldn’t rely on it as a conservation strategy.

How Divers Can Help and Enjoy Sea Kraits Responsibly

If you’re fortunate enough to encounter a banded sea krait while diving, here’s how to make it a positive experience for both you and the snake:

Stay Calm and Keep Your Distance

These snakes are naturally curious but not aggressive. Maintain at least a meter of distance. If a snake approaches you, stay still and let it investigate on its own terms. Never reach out to touch it.

Don’t Block Their Path

Sea kraits need to surface to breathe. If you see one swimming upward, give it plenty of space. Blocking its path to the surface could stress the animal and lead to defensive behavior.

Don’t Chase Them

Resist the urge to follow or pursue a sea krait for photos. A cornered or harassed snake is a stressed snake, and that’s when bites happen.

Practice Excellent Buoyancy Control

Protect the coral reefs where sea kraits hunt. Don’t touch the reef, and be mindful of your fins. Damaged reefs mean fewer eels, which means fewer sea kraits.

Be a Responsible Tourist

Choose dive operators who follow sustainable practices. Avoid activities that damage coastal areas where sea kraits breed.

Educate Others

Share your knowledge! Many people fear sea snakes unnecessarily. Helping others understand that these creatures are generally harmless (when treated with respect) reduces harmful interactions and promotes conservation.

The Bottom Line

Banded sea kraits are proof that nature loves irony. They’re among the most venomous creatures in the ocean, yet they’re so docile that divers regularly swim alongside them without incident.